Discover

This extraordinary place is famous for its amazing wildlife, stunning scenery, and superb walks. From the seasonal abundance of stunning butterflies to the shining sands of Morecambe Bay, the area is simply awe-inspiring - full of natural spectacles and a surprise around every corner.

Wells and Water in the AONB

Introduction

Left: Hawes Water, Right: Arnside Well. Images: Janet Hargreaves

There is no shortage of water in the Arnside and Silverdale AONB. It is flanked by the river Keer to the south, the rivers Kent and Bela to the north, cut through the middle by Leighton Beck and to the west is Morecombe Bay. Mud flats and Mosses, well known for their unique wildlife habitats, cover a sizeable portion of the land between. Very little of this water is suitable for human consumption, but the distinctive limestone geology creates springs and freshwater ponds which have drawn people to settle here for millennia.

Wells and the ancient settlements of the AONB

From a Mesolithic camp, dating back to 4,200 BC, found on the edge of Leighton Moss, through Roman, Viking and Mediaeval settlements up until the last century people built their homes and industries clustered around water sources for themselves, livestock, and crops. The innovation of tiled roofing and cast-iron guttering in the 19th century allowed for a more reliable supply, but it was not until piped water was routinely available that wells and springs became less important.

Victorian sanitary reforms were driven by poor health and high mortality rates in the growing cities such as Manchester and Liverpool, where sewers and piped water replaced open drains and unclean water sources, but rural areas lagged behind. Smaller, remote populations were more expensive to supply, and particularly in the AONB area the geology meant that pipelines were difficult to site.

Warton was first to have piped water in 1879, due to its proximity to a water works in Carnforth. They were quickly followed around 1881 by the Arnside area which negotiated a deal with Grange Over Sands to share their water supply via a pipe running underneath the viaduct. A cast iron maintenance hole cover on Church Hill dated 1874 suggests that the sewage pipes may have been laid earlier than this.

Cast iron maintenance hole cover in Arnside. Image: Janet Hargreaves

The steady increase in houses and tourism in Arnside following the opening of the railway in 1857, meant demand for water soon outstripped supply, causing arguments with Grange over Sands about payment and so by 1908 a new source from Lupton reservoir near Kendal was being used.

Disputes over the expense of providing water were constant and led to the Silverdale and Yealand areas waiting many more years, so it was not until 1938 that piped water finally reached them. This may explain why the greatest remaining evidence of wells can be found there.

Woodwell in Silverdale, SD 465 744, w3w/// strain.justifies.narrowest. Image: Janet Hargreaves

Wells or springs?

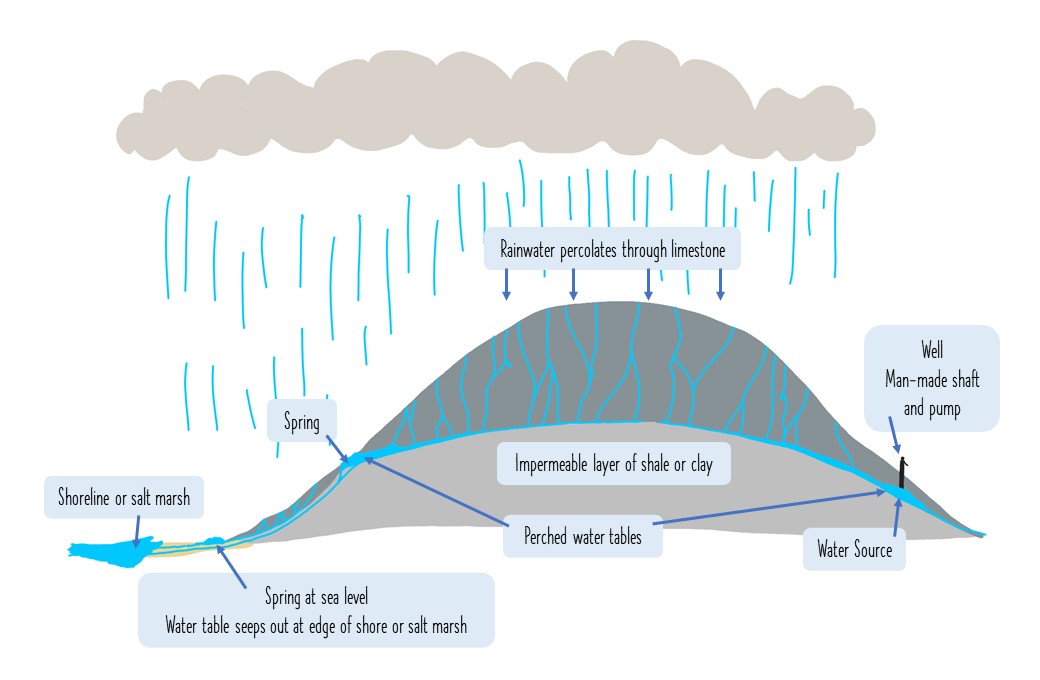

Much of the AONB sits on limestone. Rainwater filters through limestone, eroding it to cause fissures and caves until it meets denser sediments below. Here it forms into ponds, or seeps out through cracks in the limestone, or bubbles up into springs, depending on the barriers it encounters.

The largest example of a pond formed like this is Haweswater, indeed this is the largest such example of a natural pond in Lancashire. In some places such as Woodlands and Woodwell in Silverdale, springs have been enhanced by building holding tanks so that water could be stored against drought or fluctuations in need. In others, it has been necessary to dig down to the water source and a pump has been fitted, forming a ‘true well’, such as Dogslack well.

Left: Haweswater looking across to the 250-year-old summer house which has been recently restored.

Right: Dogslack well in Silverdale, one of the remining ‘true’ wells in the AONB.

Images: Janet Hargreaves

All of these sources are dynamic, changing constantly with weather, time and use. Movements in the rock, human activity for drainage and irrigation as well as the natural processes of silting up and vegetation growth mean that a once prominent well or spring may disappear completely.

Farms and larger houses were sited near to water and would have had heir own wells and ponds. Most of these can no longer be seen, although they may still be there: If you are visiting Leighton Moss RSPB visitors centre, which was formerly the Myer’s farmhouse, look back at the garden before you walk towards the hides, where you can see the old pump behind a moss-covered drystone wall.

Pump at Myers’ Farmhouse. Image: Janet Hargreaves.

However, there are many wells and ponds still to be found in the AONB, a reminder how precious and uncertain water has been for most of human existence. Looking for these is a good way to discover many of the beautiful walks on offer, and to explore the history of this unique environment.

by Janet Hargreaves

Further reading

Denwood, Andy (2014) Leighton Moss Ice Age to Present Day. Palatine Books: Lancaster

Wright, M.D. (1993) Silverdale’s Water Supply 1800 – 1940.

Barnes, Anthony J. (1903) All Around Arnside – This lovely little book was first published in 1903 and thanks to the Barnes Charitable Trust this edition was produced in 2014. It can be found in local bookstores.

Pipe, Beth & Steve (2017) Trails with Tails: Intriguing walks around Leighton Moss, Silverdale and Arnside, Palentine Books, Lancaster. – This book can be found in local bookstores. Walk 5, takes you through Trowbarrow and Haweswater, and Walk 4 ‘Leighton Wells’ includes the wells of Silverdale.

Wright, M. D. (1993) Silverdale’s Water Supply 1800 – 1940. – This detailed research study has a wealth of information about the history of water in the area.

Hawes Water Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) report